On Tuesday evening, I had my VO2 max tested. One of the guys in my tri club works over at the South Shore Harbour Fitness Center and they had all the equipment needed. I’ve always wondered what my numbers would show, so I decided to go for it this time. And as you may have seen me post on Facebook or Twitter:

Lance Armstrong’s VO2 max is 83.8. Mine is 30. Tour de France, here I come!

So what is VO2? I’m sure there’s a very complicated explanation out there if you’re interested, but basically, it’s a measure of how fit you are. More specifically, it’s a measure of the volume of oxygen (hence the VO2 nomenclature) that you consume during exercise. Higher numbers indicate that you can use more oxygen, which means you are more fit. (The units are milliliters of oxygen per kilogram of bodyweight per minute, so mine was 30 ml/kg/min.) Measuring VO2 at various intensities of exercise also shows where your body crosses from aerobic — when your heart and lungs can support all of the oxygen you need — to anaerobic — when you don’t have enough oxygen so your body starts uses other energy sources. You can only stay anaerobic for so long, since eventually you’ll just get way too fatigued to continue.

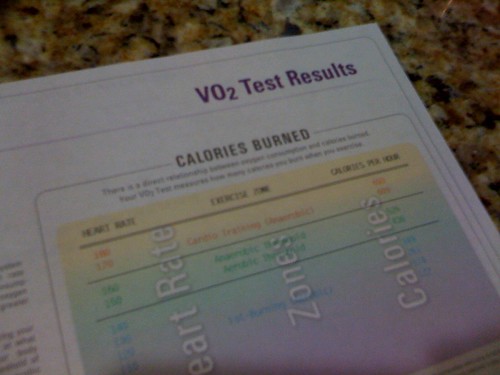

The other outcome of the test is that it provides workout zones according to heart rate — i.e. what heart rate ranges you should be aiming for during various workouts. Your target heart rate is different based on whether you’re trying to burn fat, build endurance, or improve cardiovascular fitness.

(Not me, obviously, but representative of what the test looks like. Photo from here.)

(Not me, obviously, but representative of what the test looks like. Photo from here.)

I had seen pictures of the test before, so I knew a bit about what to expect. I wore on a wireless heart rate monitor and then got to strap a lovely contraption on my face. The goal is to have every bit of air that you breathe out go through that tube so that the amount of carbon dioxide you’re exhaling can be measured, so the mask fit pretty tightly over both my nose and mouth. The test itself was much shorter and easier than I thought it would be. I assumed I’d be on the treadmill for at least 15-20 minutes and would have to run pretty darn hard, but instead it was over within 10 minutes and the fastest I had to run was 10:00/mile pace. Unfortunately, it was probably short and easy because I’m not in super great shape…

The test started with me walking at 3 mph for a couple minutes. (I should note that I’m pretty sure these paces and times vary greatly from person to person, so if you took the test, it’d likely follow a slightly different progression.) Then he raised the incline to 1 degree. Next, he raised the speed to 4 mph and I kept walking, though I was pretty close to having to run. Next he increased to 5 mph so I started jogging. A minute or two later, he increased to 6 mph. I stayed there for a minute or two, then he decreased back to 3 mph and I walked for a couple minutes. Then I was done!

I already mentioned that my VO2 max was 30. Here are the target workout zones the machine spit out:

| Low Zone | Heart Rate 114-152 | Calories/Hr 122-454 |

| Moderate Zone | Heart Rate 152-160 | Calories/Hr 454-526 |

| High Zone | Heart Rate 160-178 | Calories/Hr 526-677 |

| Peak Zone | Heart Rate 178-184 | Calories/Hr 677-727 |

These are actually consistent with what I’ve produced in the past with online calculators, although it’s nice to have confirmation. But here’s the thing — every single time I run, my heart rate averages more than 160 beats per minute. So according to those zones, I’m ALWAYS running in the high to peak zones. Does that mean I’m always anaerobic?? If so, how am I able to maintain that heart rate for half an hour or more?? I asked, and he told me that it’s possible to train yourself to be able to stay anaerobic for longer periods of time. So I guess that’s what I’ve done?? And yet by that measure, I have no aerobic base, and should be running at least some of my runs in the 130-150 heart rate range. But there’s a problem with that — I basically cannot keep my heart rate that low when I’m running.

Last night I went on a walk with Jose, because I was exhausted but didn’t want to completely skip some kind of activity. We walked over to the neighborhood pool and back, a total of 2.25 miles in 40 minutes. My average heart rate was about 115, so that’s too low. Yet running — at least in the manner I’m used to — gets my heart rate too high. So what am I supposed to do if I’m interested in trying heart rate training and building that so-called “aerobic base?” MAYBE I maintain something in the low-to-moderate zone it if I run/walk, and the run is something like a 13:00-14:00/mile pace. But running that pace makes me feel lazy, bored, and unproductive. Hmm.

For reference, things are more normal on the bike. During last weekend’s 50-mile ride, my average heart rate was 156, right smack in the middle of the moderate zone (and that was despite all the wind).

For now, I’m just going to keep doing what I was doing. But in the meantime, I’m going to do some reading on heart rate training. Who knows, maybe concentrating on low intensity workouts could actually benefit me…

The run/walk approach is a good way to keep your average heart rate in the right zone while you build that aerobic base. I did that a few years ago when I was working with a coach that was All About The HR Training, and it worked out really well (although it was annoying as all get out to do).

Another idea is to walk on a treadmill, but kick up the incline. That’ll get your HR up into the right range, but the downside is that you’re on a treadmill.

Having done the testing, would you say it’s valuable info? I’ve been pondering getting mine tested, but it’s a little pricey so I’m still on the fence.

That all sounds a bit like malarkey to me. I’m no health expert, but it would seem that if you cross some arbitrary threshold where your body no longer gets enough energy from heart and lungs, then whatever other source of energy it taps is certainly not making your heart and lungs stop working and getting stronger. Also, if you want to be able to run faster and farther, then building an “aerobic base” by running slower and shorter doesn’t seem like it would help you reach your goal. If exercise is meant as a way to stay active and get in shape, then targeting certain heart rates doesn’t seem that important, especially if the targeting seems to tell you that running at a pace you’re comfortable with is not keeping you in an “ideal” zone. Also, the biggest variable in that equation is your weight. Should you be targeting certain metrics that are based on weight when your goal is to lose weight? Instead of reading more about this mumbo jumbo, I would just hit the bike for an extra 5 minutes.

Dawn, it was interesting, but I hesitate to say it was completely worth the money. Online calculators have given me VO2 max values of 28-32 based solely on a recent 5K or 10K race time, and similar heart rate zones. So in a way, I feel like I didn’t actually get any new information, although it was nice to get “official” confirmation.

Brian, I don’t think it’s completely bunk. There’s a LOT of science that has gone into this kind of stuff.

But it definitely depends on what your goals are. It’s not saying I should do ALL of my runs with a lower heart rate; it’s saying that doing some of them slower would increase my aerobic base. If all my runs are done anaerobically, I’m not improving my heart and lungs as much as I could — instead, I’m just training my body to go longer in anaerobic mode.

Most of the science says that if you spend time building the aerobic base, your VO2 max will increase and you will therefore get fitter and faster. It’s not “go slow to get fast” but rather something along the lines of training at a variety of intensities instead of just at one speed all the time.

Yea, I read some stuff about it. It doesn’t seem like total malarkey now, but it does seem like overkill for most recreational athletes, especially when your primary goal is to lose/maintain weight. I see this sort of thing as useful for pros and people already at exceptional levels of physical fitness, but for you and me it has limited application.

I’d just wait a few weeks until the temp and humidity goes through the roof. That should be enough to raise your HR by 10-15 bpm.

I think this is extremely interesting (not necessary for a recreational athlete – but very cool to know). Hooray for numbers and data!

Didn’t you run a half marathon at about 10:30 or 11:00 pace? It seems crazy to me that you could run a 2 hour race anaerobically, but maybe I’m totally off base.

I do most of my training at 10:00 pace or so, but I can race at 7:30 for a 5K. (I don’t track my heart rate.) You have much closer speeds for training and racing, I think. So maybe you could do your training slower. For me, running closer to race pace is just too hard; it de-motivates me to run. 10 mpm is kind of the sweet spot – slow enough that it’s not too hard, but fast enough that I’m not bored.

If training at 10 – 11 minutes pace feels good to you, I’d keep right on doing it. I think the most important thing is to run, and however you like doing it, I’d stick with that. However, what this tells you is that you could slow down and still get value out of your workouts.

Random interesting quote: ‘According to Jack Daniels: “Anaerobic Threshold is the pace or intensity beyond which blood lactate concentration increases dramatically, due to your body’s inability to supply all its oxygen needs. As you get fitter, your red line rises from about 80 percent of maximum heartrate to 90-95 percent. “Physiologically, threshold training teaches muscle cells to use more oxygen–less lactate is produced. Your body also becomes better at clearing lactate: Race day red line speed rises.”‘