MAN ON THE MOON

July 20, 1969

An estimated 1 billion people on the planet Earth are watching or listening to transmissions from the Apollo spacecraft in lunar orbit. All three U.S. television networks are on live. At 1:30pm U.S. Armed Forces Network radio is on live. In lunar orbit, Mike Collins has taken the controls of the Command Ship Columbia and gently undocks from the lunar lander, the Eagle.

In train stations and bus stations, ballparks and airports the sounds coming from the moonships and the crackling static are heard around the country. Briefly, for a fleeting moment in time, the entire American nation has come together as one to follow an event, not a national tragedy but a voyage of exploration: humans on their way down to the surface of an alien world.

“The Eagle has wings!” cries Buzz Aldrin. Slowly Columbia and Eagle pull away from each other but remain in the same orbit.

Now with both craft on the back side of the Moon, the Eagle’s engine fires up and begins to break the craft down into a lower orbit. The engine fires at 10 percent thrust for 15 seconds, then is gradually increased up to some 40 percent of its 9,970 lbs of capability.

The crew is flying with their feet first, face up. The craft speeds across the barren landscape below just 60 miles up with a low point of eight miles. At that low point they are to fire up for the final descent burn, riding a rocket’s tail of hot gas towards the lunar landscape.

Columbia’s Mike Collins calls the ground and reports that the Eagle is “on its way down” towards the surface. At 260 miles uprange from the touchdown point, the LM’s rocket engine fires again for its final burn, or PDI (Powered Descent Initiate). Now Eagle is dropping from 50,000 feet above the Moon to a low point of 10,000 feet. The engine is powered down to 6,000 pounds of thrust. But now, at 39,000 foot altitude, things begin to go wrong.

On the instrument panel, the Caution & Warning System alerts the crew that they are close to radar lockup. If this happens, their radar system will be unable to guide them towards the landing site. The crew quickly resets the switches for the system, and it returns to normal.

At 9,620 feet, the craft’s computer begins to send a series of alarms to the crew. These “1202” alarms warn that the computer is becoming overloaded with data inputs that are taking too long to process. Armstrong clears the computer’s memory and asks Houston control for a judgment call. Mission Control calls the crew: go!

Just above 2,000 feet Armstrong takes manual control of Eagle briefly to check out the flight controls. The spacecraft is snappy and responsive. Below 1,500 feet, the astronauts are now scanning the landing site below. What they see concerns them. The autopilot is bringing Eagle down into a boulder-strewn field. At 500 feet altitude, concerned that the landing site is not suitable, Armstrong reaches over and takes control of the spacecraft away from the autopilot and the computer: he is flying the Eagle.

Using the ascent stage thrusters, Armstrong brings the Eagle laterally across the surface looking for a landing site. At 100 feet he stops the rate of descent, then begins it again slowly.

At 30 feet, peering through a cloud of dust stirred up on the surface of the Sea of Tranquility, Aldrin calls out that Eagle has less than a minute of fuel left in its tanks. Should they abort? Peering through the clouds, Armstrong sees a smooth area through a break in the dust. He has moved more than 1,100 feet across from the original landing point as chosen by the computer. Armstrong is still looking out the window when Aldrin calls: “Contact Light!” A small light has illuminated on their instrument panel, indicating that a probe in one of the LM’s footpads has touched the alien lunar soil.

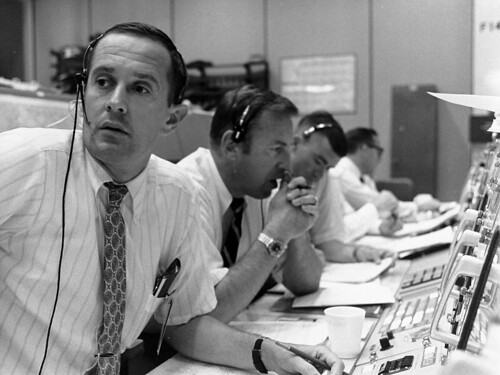

With the engine still running, the LM drops down onto the surface. Armstrong shuts off the descent engine. All is quiet. In Mission Control Capsule Communicator Charles Duke calls to the crew “we copy you down Eagle?” At first there is only static. Then Armstrong calls across the generations: “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed!”

On the east coast of the United States it was 4:18pm EDT. In Yankee Stadium in New York, 16,000 people rose to sing the national anthem as they stopped a baseball game in progress. At Grand Central Station, the thousands of Sunday travelers cheered so loud Aldrin’s last words before touchdown were not heard. In Trafalgar Square, London announcers screamed “the Americans have done it!” In Japan, television viewers were told “a new age has now begun.” In Mission Control Houston, flight controllers come to their feet cheering, breaking a tradition of silence.

It had been nearly exactly 8 years, 2 months since John Fitzgerald Kennedy had walked up the center aisle of the U.S. House of Representatives and made the lunar landing a national goal. In his CBS News control booth, newsman Walter Cronkite cannot speak. He turns to astronaut Walter Schirra and then says: “Man on the Moon!” It is Sunday, July 20, 1969.

The mission has been accomplished…

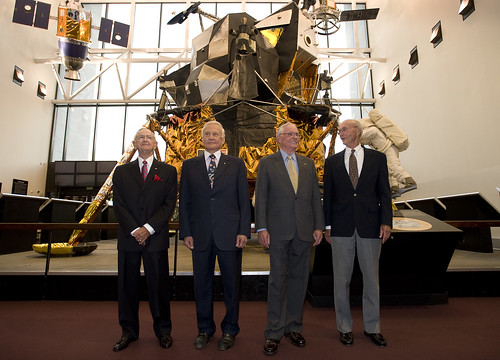

Mission Control founder Chris Kraft with Apollo 11 astronauts Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins at the Air & Space Museum on July 19, 2009

Great post Sarah! I will forever be in awe of this accomplishment and what the US space program was able to accomplish that decade! Amazing stuff! I can’t even imagine what it must have been like to watch that live on TV and how proud I would have been of our country and our Astronauts.

I agree Christy — it must have been so cool to see it live. Alas, half the population is too young to have seen it.

(As a side note, I didn’t actually write what’s above — I copied it from an email that circulated around work. I don’t know who the original author is.)